Brecon Beacons – The high life of South Wales

Pen y Fan is the highest point in South Wales and a mecca for its denizens, with two million people living within an hour’s drive of the national park and seemingly born with the innate desire to stand on its top. The mountain also attracts walkers from far and wide, the National Trust now estimating that half a million people attempt to climb the mountain every year, visitor numbers having doubled in the last five years.

The summit may be the cynosure for the masses and rightfully worthy of high praise, yet it is merely the loftiest point on an extensive serpentine ridge of outstanding character, which provides the backbone to the central Brecon Beacons massif, one of four principal upland ranges in the Brecon Beacons National Park.

These ranges exhibit striking geological formations, with major collective similarities, particularly distinguished by sandstone plateaux abruptly terminated by steep north facing slopes, leading to deeply incised valleys that contrast with gently tilted ridges descending to the south. For the purposes of this ‘Worthy’ our focal area is extensive, including the summits surrounding the Taf Fechan Valley, the northern offshoot ridges and the plateau east from Fan y Big, culminating at Carn Pica. All the tops can be accomplished on a long, single day outing, although the northern ridges offer much of interest and make fine circuits in their own right.

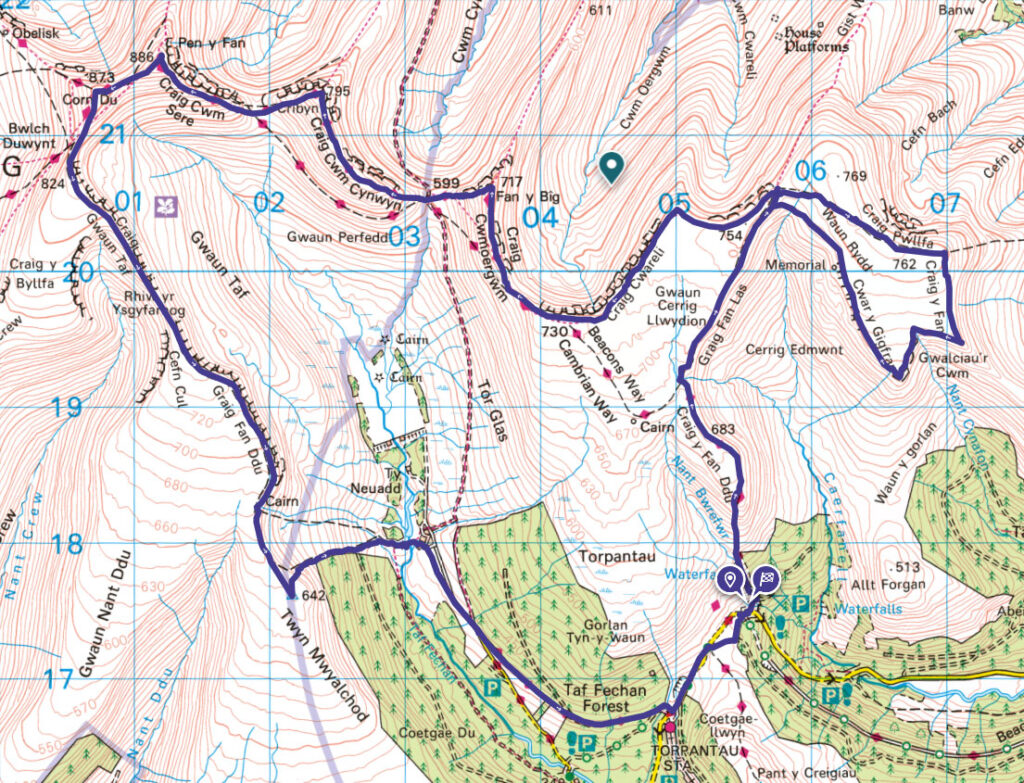

The map can be zoomed in or out to change the scale

The Western Massif

Let us commence with Pen y Fan, or for those in the know, the mountain is nicknamed ‘The Fan’ (pronounced Van). Of all Britain’s landmark highest points, Pen y Fan is the easiest to climb and by far its most trodden ascent is that from the west, which basically commences at the top of a pass half way up the mountain. The much enlarged National Trust Pont ar Daf car park boasts 260 spaces, although this is still well short of the numbers required on anything but a wet midweek winter’s day. There is further parking at nearby Storey Arms, which fills up equally rapidly. The ascents from this side are the least attractive, in truth being merely average walks with a fine view from the top. However, being the shortest climb makes Pont ar Daf a so-called ‘desire line’ in modern language and that guarantees popularity. Indeed, most people from here go up and down the same route, which indicates that attaining the summit is the major objective, not the quality of the walking experience. Unsurprisingly, this route is commonly known as ‘the motorway’.

The alternative path from Storey Arms is a little quieter and can be easily combined with Pont ar Daf to make a circular outing. Storey Arms as a building was, as the name suggests, an old coaching inn, although this was demolished in 1924. Nevertheless, the name was carried forward when Cardiff Council created the outdoor education centre here in 1971. The ascent from Storey Arms is known as the military route, a reminder that the Brecon Beacons have long been a training ground, in particular for the Special Forces who carry out a twice yearly (winter and summer), four-week long endurance selection process for the SAS.

One part of this testing process was originally called the Exercise High Walk, now blessed with the more catchy title of The Fan Dance. This involves a heavily laden out and back trial from Storey Arms over Pen y Fan to Bwlch ar y Fan following the Beacons Way (the summits of Corn Du and Cribyn are not included), down the Gap Road to Torpantau Station then turning round to retrace the route. Since 2013 a public race (with slightly less heavily-laden competitors) emulates this, with the aim being to complete the sixteen miles in under four hours. There are variations and extensions including lightweight ‘Clean fatigue’ trail running and races at night.

For those who are looking solely to climb Pen y Fan, the approaches from the north are infinitely finer than from the west. All utilise splendid grassy ridges, which can be combined to make horseshoe walks. Cwm Llwch boasts a jewel of a glacial lake, the solitary example in the central Beacons. Naturally this has spawned several legends, including one of the more charmingly inventive, which claims there is an invisible island in the lake with a magical garden created by fairy folk. A secret door opened on May Day only, inviting humans to visit but to take nothing but memories back home. Of course, there’s always a rotter to spoil it and he stole a flower, only for him to go mad and the door never to be reopened. Above the lake the ridge is attained, joining the path from Storey Arms at an obelisk dedicated to the memory of Tommy Jones, a five-year-old who in August 1900 got lost in the lower part of Cwm Llwch. Despite continuous searching he was not found for twenty-nine days mainly because no one thought he would have ascended so high.

The ridge of Cefn Cwm Llwch is a magnificent ascent that boldly leads directly to the summit cairn of Pen y Fan. The final part is quite steep although without difficulty except when icy. The top section does look rather unlikely when chosen for descent, something much compounded in mist. For these reasons, there is a path of avoidance, traversing across from the shallow col between Pen y Fan and Corn Du that links to the ridge below the steep section.

On most days of the year the summit will be bustling with jubilant pilgrims in trainers queuing for photographs by the National Trust plaque secured to the cairn. To be fair, so much work has been expended on path restoration (around £100,000 a year is allocated for maintenance in these hills) that trainers are perfectly suitable footwear in fair weather. However, few summiteers trampling on the cairn realise that this (and the one on neighbouring Corn Du) is actually a reconstructed Bronze Age burial cairn from around 2,000BC. Both cairns were suffering badly from human erosion, especially Pen y Fan, as the trig pillar had been erected on top of the cairn, which naturally encouraged additional footfall. Furthermore, many stones were being purloined by the army for use in temporary shelter building during training exercises. In 1991 the cairn on Pen y Fan was in such perilous order that an emergency excavation took place, the summit trig point removed and the cairn rebuilt.

Corn Du can be viewed as a sister summit, almost identical in its decapitated appearance. Pen y Fan stands at 2907ft (886m) with Corn Du slightly lower at 2864ft (873m). The views from both summits are profoundly uplifting, exuding a character unique to the Beacons. It can be difficult to absorb this on busy days, although nowhere else in the range will you encounter such crowded scenes and, remember, these are just two tops amongst many throughout the massif.

For discerning walkers Cribyn is the equal of the higher Pen y Fan, from where it displays an audacious profile. Cribyn attains 2608ft (795m) in an elegantly pointy fashion and is the third highest of the main range. This is fitting, for the mountain forms an integral part of the iconic skyline formed by the Beacons when viewed from the north. The prospect of Cribyn from Pen y Fan is majestic and the reverse from Cribyn equally so, these visions dominated by the extraordinary strata of the north facing craggy slopes. The two tops are initially linked by the ridge of Craig Cwm Sere which steeply plunges 221m before a reascent of 130m attains the summit of Cribyn. Craig Cwm Sere comprises the most substantial drop between mountains in the Brecon Beacons and has been christened Jacob’s Ladder. The path consists of pitched stone for much of its length and keeps just back from the edge, although it is worth venturing to the brink to marvel at the spectacle of Pen y Fan’s northeast face at close quarters. Whilst the rock is too friable for summer climbing the crag offers fine winter sport.

Cribyn is rarely an objective in itself but does provide an excellent short day walk. From the north Bryn Teg is a typically wonderful Beacon’s ridge with a customarily steep finish, again arriving directly at the summit cairn. Turning our eyes to the east across the head of Cwm Cynwyn is Fan y Big, a smaller version of Cribyn. The two hills are separated by the Bwlch ar y Fan, a high pass for an ancient trade route, standing at 599m. This track is possibly Roman in origin, although there is no definitive evidence of this. It was certainly used by horse drawn carriages. It is known as the Gap Road and remained classed as a road (although only suitable for off-roaders!) until the National Park Authority removed this status to protect the landscape, nonetheless, the trail remains popular for mountain biking (and Fan Dancers!).

Fan y Big can once again be climbed by a ridge from the north, the Cefn Cyff, which leads to the celebrated summit feature known as the diving board, being a horizontal rock slab, thankfully wider than a swimmer’s diving board, that provides a focal point for photographers. At 2351ft (717m) this is an appreciably smaller hill than the main Beacons and in reality is not an individual peak but merely a spur of the Craig Cwarelli/Waun Rydd plateau.

The Eastern Massif

Fan y Big marks the transition to the eastern range of the Beacons, providing fascinating walking particularly when following the perimeter paths above abrupt scarp slopes.

The nomenclature of the eastern range is rather confusing. From Fan y Big, the ground barely dips along the ridge heading due south before gently rising and broadening onto the table top of Gwaun Cerrig Llwydion, with a high point of 730m. There is a clue in the name as to the nature of this plateau for the translation means bog of the grey rocks. However, boots will remain mostly dry by sticking to the edge of the spectacular escarpment of Craig Cwarelli (a name often used for the mountain itself), until the high point of 754m is reached. This is known as Bwlch y Ddwyallt. In most people’s minds a bwlch is a col, not a high point and indeed there is a slight dip beyond forming a high pass between the headwaters of Cwm Cwarelli and Blaen y Glyn valleys and also linking to the Waun Rydd plateau beyond. Waun Rydd is the highest point of the eastern massif at 769m.

Ridges exist from the north and east but most often the plateaux are accessed from the south at Blaen y Glyn Forest, itself renowned for a series of splendid waterfalls. There are also possibilities from the south to combine all the mountains of the central Brecon Beacons into circular walks. The standard Brecon Beacons Horseshoe confines itself to Pen y Fan and its satellites, beginning at Taf Fechan Forest. The outward leg is either the Gap Road, a gently angled stony trudge that is nevertheless accomplished rapidly, or the ridge on western side of the former Neuadd Reservoirs. This is steep to start but then extraordinarily easy angled, leading eventually to Corn Du. If going this way, don’t forget after the initial pull to divert briefly to the top of Twyn Mwyalchod. The summit boasts the only surviving trig pillar in the central Beacons and offers a fine viewpoint for the prospect of the walk to come.

The Upper Taf Fechan until recently held two reservoirs both now drained due to increasing instability of the late Victorian dams. The cost of repairs outweighed their usefulness. The grandiose edifice of Upper Neuadd dam remains standing due to having acquired listed building status through architectural significance and is a bizarre sight, evoking a fantasy gateway to a lost world. The upper reservoir stood at over 1500ft and was the highest in the Brecon Beacons. It was drained in 2016 and the lower reservoir in 2021.

Effectively the Beacons Horseshoe is a circuit above the reservoirs, a walk of around ten miles but the lofty starting point makes this merely a half day outing. Nonetheless, the horseshoe can be extended (omitting the Gap Road) to include some or all of the eastern Beacons.

By utilising tracks through the Taf Fechan Forest to the minor road at Torpantau, the circuit can be linked to Blaen y Glyn Forest. In this case the route is recommended anticlockwise to best enjoy the breathtaking escarpment approach from Bwlch y Ddwyallt. A round of Waun Rydd is an additional option for those determined to bag every major summit. Enroute you will encounter wreckage of a Wellington Bomber and a memorial cairn commemorating the five Canadian airmen who failed to clear the Waun Rydd plateau in the mist in July 1942.

The full round is 15.5 miles (25km), which can be shortened by omitting Waun Rydd to 12.5 miles (20.5km). A further shorter alternative, saving a mile or so is to cut across the plateau from Craig y Fan Ddu along the Beacon’s Way. The downside is excluding the escarpment of Craig Cwarelli, although the compensation is the bonus of curious terrain on the plateau, exhibiting a vast, exposed area of gently inclined rock slabs. Whichever option you take, this is a walk with great variety including forests, waterfalls and the phenomenal impact of the mountain escarpments. Do it, it’s fantastic!

Worthy Rating: 84

Aesthetic: 25.5

Complexity; 18

Views: 16

Route satisfaction: 16

Special Qualities: 8.5

2 thoughts on “Brecon Beacons – The high life of South Wales”

A range I have been to many times and yet so much to learn from your well researched essay. Thanks

Thank you Adrian, that’s very much appreciated!