The Great Ridge: Walking the boundaries of ancient and modern

Mam Tor is a social media phenomenon, although most of the 700,000 visitors who stand upon the summit every year have no knowledge of the geologically complex and historically significant land beneath their feet. The hill may be the focal point of Derbyshire’s Great Ridge, although many do not progress beyond Mam Tor’s trig point, yet even the generally acknowledged span of the ridge for those that do sells it short.

It has to be said that the overwhelming popularity of Mam Tor is mostly due to it being a fifteen-minute walk from a high road pass, something that would generally mark it down in the Worthy stakes, however, here we are talking about the Great Ridge, being not merely the celebrity focus of Mam Tor, but a chain of summits stretching for five invigorating kilometres.

The name Great Ridge is a relatively modern appellation, bestowed by W.A Poucher in his 1946 guidebook Peak Panorama. It was an inspired marketing tactic, if a rather grandiose title for a relatively low level, technically straightforward walk along an elegant crest that continually provides stimulating views. Poucher flamboyantly applied Great Ridge to the section between Lose Hill and Mam Tor, a natural hill barrier separating Castleton from Edale. However, geographically, the crest extends westwards along Rushup Edge to even higher ground at Lord’s Seat, from where, abruptly, the character changes to become broad, open moorland.

It is this extended ridge we are exploring in this feature, which in the fashion of Poucher perhaps we could dub the ‘Greater Ridge’. To be fair to Poucher, his definition of the Great Ridge was ambiguous, not directly including Rushup Edge, although he did suggest that everyone ought to walk its length.

Let us commence at the eastern top on the ridge, Lose Hill, standing at 1563ft (463m) and easily reached by a variety of paths from Castleton or Hope that converge before the summit. The origin of the name is unknown, although it is curious that facing Lose Hill across the valley is Win Hill and this has naturally spawned spurious folk tales. The upper slopes are also known as Ward’s Piece, after Bert Ward, founding father of Sheffield ramblers and an active campaigner for access to the hills (see Kinder Scout feature). In 1945 the Sheffield Ramblers Association raised funds to purchase fifty-four acres around the summit of the hill and presented it to Ward for his service to the cause. Bert subsequently gifted it to the National Trust.

Lose Hill is where we first meet ancient history on this walk, as the shallow mound on the summit may be natural or created as a Barrow, a burial mound, and there are unsubstantiated claims that human remains have been unearthed. As we will discover, prehistoric human occupation on the Great Ridge is one of its major features, whether or not Lose Hill is part of the story.

To the side of the mound is a circular toposcope indicating surrounding hills and from where our yellow brick road along the crest of the Great Ridge commences. Such flagstones are a frequent walking surface on the ridge, a necessary evil to protect the hills from the widespread erosion of footfall, although they do take away some of the wilderness feel of the hills. The paths have been restored in phases over many years and generally the stone has been locally sourced from the floors of abandoned mills in the area, effectively returning the stone back to the hills from whence it came.

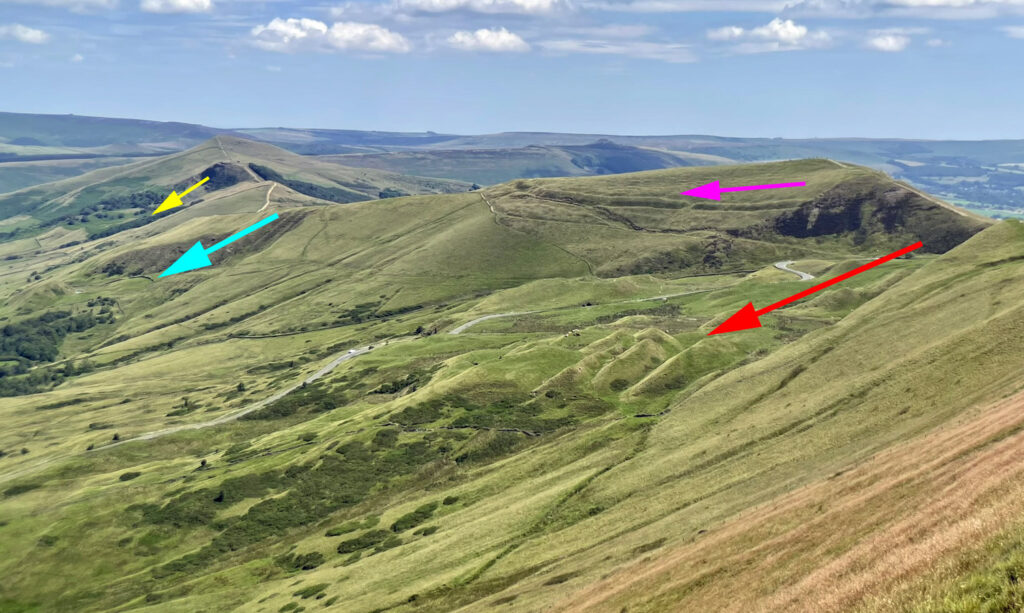

A gentle stroll leads to Back Tor, a rather spectacular perch above a precipice that plunges into Backtor Wood, unusual in that the trees have colonised hummocky ground caused through a landslip on the same scale as the much celebrated event on Mam Tor. More on that shortly.

The descent from Back Tor is short and steep to a depression where a cross path from Edale to Castleton traverses the ridge. We continue, ascending a graceful rise to a gentle summit with no name on the map, just a spot height of 426 metres. We are on the way to Hollins Cross so some people call it Hollins Hill, although that is confusing as there is already another Hollins Hill a few miles to the south of Buxton. Others refer to it as Barker Bank, which the Ordnance Survey attributes to the slopes on the south side. A glance at the 1883 OS map names this part of the ridge Lidgate Bank, so take your pick. This section of path is one the most recently restored, achieved in 2021 through a large fundraising campaign, initiated by the British Mountaineering Council’s Mend our Mountains campaign. Around five hundred metres of badly eroded path was repaired from Back Tor to Hollins Cross, our next destination.

Hollins Cross is the lowest point on the Great, or indeed Greater Ridge. It was the major crossing point linking Edale and Castleton by means of a ‘Coffin Road’, so-named as the route of burials bound for Castleton (and Hope). Edale did not receive consecrated ground until 1634 and indeed was a backwater settlement until the Victorian railway arrived. To mark the passage a holy cross was erected on the col and extant until around 1900. Hollins Cross is now marked by a memorial to Tom Hyett, another respected member of the Ramblers Association.

As we approach Mam Tor the devastation on the hillside beneath the summit becomes increasingly apparent, the hill being one of the most active inland landslide districts in Britain. The main failure occurred as a single, catastrophic event about 3600 years ago, but remained unstable, frequently suffering minor slipping to this day and predicted to continue. The reason for the landslides is due to the solid sandstones that comprise the upper one hundred metres or so of the hill being underlain by unstable shales, made even more precarious at times of prolonged wet weather.

There are four landslip sites on the Great Ridge with Mam Tor being the most accessible, mainly because, somewhat unwisely, a road was built on top of the spoil! This was constructed as a coaching route in 1810, the landslip presumably being considered inactive at the time. Records have been kept since 1907 and detail sixteen separate landslides over the subsequent sixty-six years, most requiring only minor repairs to the road. However, December 1965 witnessed the largest event, causing the road to drop six feet in the upper reaches. Eventually in 1997 the council admitted defeat and closed the road permanently. Now known as the Broken Road, it is easily visited on foot and provides a thrilling spectacle.

From many perspectives Mam Tor is a powerful sight, the majesty belying the modest altitude of 1689ft (517m). The hill has become one of the sunrise and sunset capitals of social media, more for the ease of access than the quality of the solar experience, with many other local viewpoints being considered superior. Social media will also tell you it is called the Shivering Mountain (a fine marketing exercise on the landslip theme) and that Mam Tor translates as Mother Hill, as though it was an ancient sacred height, although some claim the name derives from having spawned many hillocks, these diminutive offspring (as at Back Tor formed by landslips) clustered beneath its slopes. Furthermore, Mam is not the original name as old maps from the 1600’s call it Man Tor.

Mam Tor summit is the only section of the ridge from Lose Hill to Lord’s Seat that is briefly wider than an otherwise narrow crest. This caught the eye of ancient man. Stand upon its domed top and take yourself back nearly three thousand years to a time when the landslip may still have seemed fresh in the air. As today, all around there would be people, the difference being that these folk were living in one hundred wooden roundhouses on the very top of the hill. This was a Bronze Age settlement inhabited from around 1200BC, later to be converted into an Iron Age hillfort that covered sixteen acres and itself occupied until around 400BC. People lived on top of Mam Tor for eight hundred years!

Most present day visitors huddle around the stone trig point, in excellent condition considering the numbers that balance on its top and that it has not been maintained by the OS since 1970. The summit has seen much stone laid to protect it from heavy footfall and, even though many people do not know about the hillfort, they unwitting trample all over its ditch and ramparts, so the National Trust have undertaken much recent restoration work to ensure its survival.

Beyond Mam Tor, the ridge continues onto Rushup Edge. There is a sharp stepped descent to Mam Nick, which is exactly that, a nick in the skyline. Importantly, this lofty natural col has an altitude of 455m which is higher than most parts of the Great Ridge and further underlines that Rushup Edge should be considered intrinsically part of the ridge. Mam Nick is merely an artificial boundary. In fact, the pass was formed by the landslips and prior to that was actually forty metres higher, therefore much less of a gash than it is today. Incidentally, the fourth landslip site is at Cold Side, just north east of Mam Tor’s summit. The Mam Nick landslip covered twice the extent than that on Mam Tor’s southern slopes and is again utilised by a road, a splendidly scenic drive that exits the Vale of Edale.

Lord’s Seat is the highest point of Rushup Edge (and the Greater Ridge) at 1804ft (550m) and best reached by keeping to the narrow crest rather than the main path in order to savour the finest views. The summit exhibits a round, flat-topped earth barrow fifty-five feet in diameter and seven feet high. This was, more certainly than Lose Hill, a burial chamber predating the Mam Tor settlement by a century or more. This means that someone may actually have been up there when the first major landslips occurred! The mound has made for a convenient viewing platform for modern walkers, eroding the chamber’s roof so the barrow is now fenced off. There are no records and no signs of an excavation (a thriving pastime in the 1800s) and, as it is now in hands of the National Trust, its preservation is hopefully secure.

As for Lord’s Seat as a name, it is thought the lord in question was William Peverell the Norman Lord who constructed his titular castle in Castleton. Beyond the summit, the ridge abruptly broadens into gritstone moorland and forms a geological terminus of the ‘Greater’ Ridge.

For those returning to the historic village of Castleton there is another geological boundary to cross into limestone country. The area flourishes with a wide variety of caves and lead mines, and certainly a visit to the dramatic gorge of Winnats Pass should be on your itinerary.

Edale Skyline

The continuation of high ground from Rushup Edge onto Brown Knoll sweeps around onto the mighty Kinder Scout, eventually running out of steam at Win Hill, directly opposite our starting point of Lose Hill, yet twenty miles on foot if tracing the skyline of the Vale of Edale. As a long day’s walk it is the finest outing in the Peak District, the terrain being generally not too taxing and the ground can be covered surprisingly rapidly.

The Skyline is also an organised race, founded in 1974. Initially sponsored by local climbing shop owner Don Morrison, it has carried his name as a memorial following his death in the Karakoram in 1977. The race route is longer than the walk and involves more ascent, as the starting point is Edale, which effectively means the runners climb Kinder Scout twice! Most walkers choose a point on the direct route, Hope village being the most common place. Otherwise the route is similar, although the race no longer visits the summit of Mam Tor to help reduce erosion, so follows path below the top on north side. The event takes place in late March so the weather can be very variable, although a dozen or so elite runners usually complete the circuit in under 3 hours with the current record being 2.34. That would be a pretty decent time merely for a walking circuit of the Great Ridge from Castleton!

Worthy Rating: 70

Aesthetic – 22.5

Complexity – 12

Views – 14

Route Satisfaction – 13

Special Qualities – 8.5