Triangulation Matters: Monuments of map making

Hill tops are fascinating places, often being adorned with fine cairns, monuments and, very frequently, trig pillars. Such structures can provide significant narratives in the chronicles of a mountain adding one of the many aspects of human interaction with the heights.

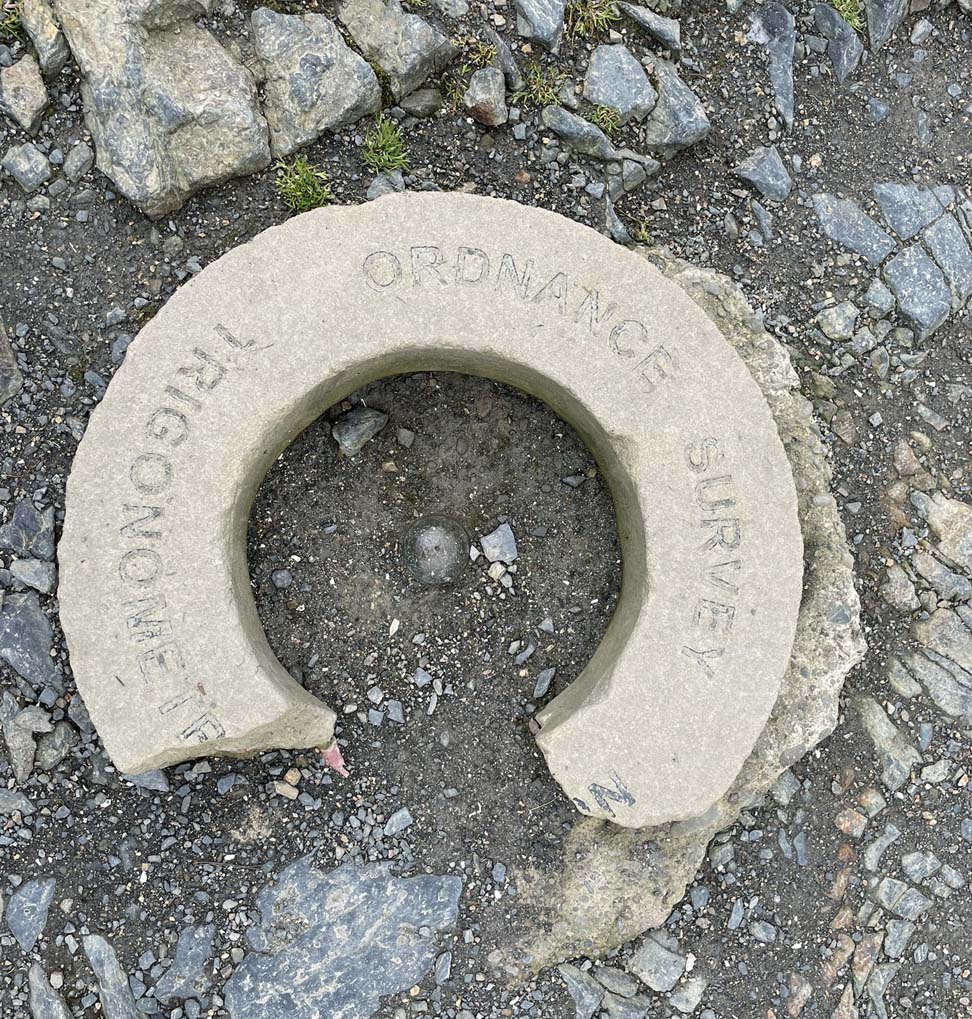

In this feature we are going to explore trig points, or Triangulation Stations, which manifest in several forms, although it is the trig pillar that is such a familiar landmark to hillwalkers, marked as little blue triangles on OS maps, yet their intriguing history may be less so. Their full name is Ordnance Survey Triangulation Pillars and, whilst most are now entirely obsolete, they were built for a very important purpose – to map Great Britain and Ireland. Triangulation was the method employed to achieve this purpose and is basically a mathematical calculation of position and distance using a network of triangles.

BACKGROUND

Until the mid-1700s maps were not particularly accurate and this posed a problem for military strategy, something that had become especially apparent during the Jacobite Risings. Nevertheless, it was not until 1791 that an initial ‘Principal Triangulation of Britain’ was undertaken.

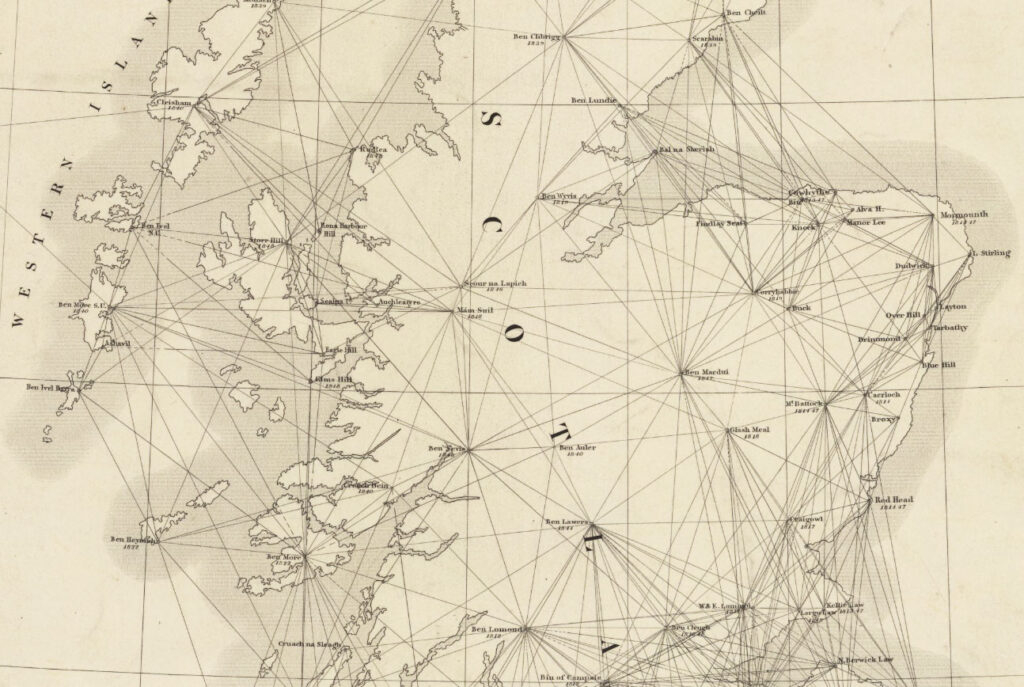

Map reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

This triangulation focussed primarily on spatial location, not altitude, which was considered less important. Up until that time, mountains had been avoided as being fearful places. This was gradually changing as scenery began to become appreciated as meritorious, with hills being climbed for pleasure rather than simply getting in the way when travelling from one place to another. However, most mountain heights were guesswork and reading Wordworth’s ‘Guide to the Lakes’ from 1810, it becomes apparent that it was assumed at the time that Scafell was higher than Scafell Pike when the poet first climbed it. What Wordsworth called the ‘Pikes of Scawfell’ was not even named on some maps of the day!

Nonetheless, developments were afoot; the concept of contour lines becoming established as a by-product of the studies on Schiehallion in 1777 into calculating the mass of the earth, although it was not until 1841 that the first ‘Primary Levelling’ of Britain was undertaken. Levelling is a surveyors’ term for measuring height relative to known points, these originally calculated to be above the mean tide level at Liverpool. Later, and still in current use, the mean tide at Newlyn, Cornwall became the principal baseline. Again, mountains were not high on the agenda and, amazingly, it was not until 1847 that Ben Nevis was confirmed as the highest mountain in Britain. Prior to that Ben Macdui had been thought to be the other major contender. Incidentally, Mount Everest’s height was calculated in 1856 to be the world’s tallest, the result being exactly 29,000 feet. It was decided to deliberately add a nominal two feet to make 29,002ft, so that the public did not think the precise measurement was merely a rounded estimate!

For levelling, ‘Benchmarks’ were created by cutting horizontal slits into all manner of structures to provide a ‘bench’ to hold the levelling apparatus, with at one time over half a million around the country. The most accurately measured were afforded the title Fundamental Benchmarks, each set on stable ground and around twenty-five miles apart. Since that time two further Primary Levellings have taken place, the latest being from 1951.

RETRIANGULATION

Britain and Ireland’s first accurate maps were produced through the Principal Triangulation, which was a piecemeal affair lasting until around 1850. Very few mountains actually served as Principal Triangulation Stations, for example in the Highlands, only those with far-reaching views were chosen to reduce the number required, with only around ten summits ranging from Ben Klibreck in Sutherland, to Ben Lomond in the south. By the 20th century, an updated, more detailed framework was considered desirous and in 1935 the Retriangulation of Great Britain was commenced. Delayed for ten years by the war, it was completed in 1962, leading to the grid reference system we use today.

The project was led by Brigadier Martin Hotine on behalf of the Ordnance Survey, who designed and installed a new network of over 6,500 triangulation pillars, most but not all being tapered four-sided concrete structures, named Hotine Pillars. These were fabricated to be solid supports topped by a brass bracket called a Spider to which a theodolite could be attached. The location was chosen so that at least two further pillars could be seen, thus dividing the country into a series of triangles.

Trig pillars were erected in four separate series beginning with 378 primary pillars, then filling the gaps successively until sufficient accuracy for the triangulation was complete. For example, within the Lake District mountains there were four initial primary trigs on Black Combe, Scafell Pike, High Street and Skiddaw. Approximately twenty-five secondary trigs were then added, followed by around nine tertiary trigs. No fourth order stations were required.

For such a mundane looking structure the construction of a Hotine pillar was surprisingly elaborate with more going on underground than might be imagined. The pillars were 4 feet tall with at least 2ft 6ins buried subterraneously. In general, around two tons of sand, cement and aggregate was required, all needing to transported to the site and, as so many were located on remote mountains, trigs could take from three days to three weeks to erect. In some places former military ‘Weasel’ all-terrain tracked vehicles were employed to transport materials and in later years helicopters provided the most efficient service. Also ease the burden, some pillars made use of local stone which on occasions was a stipulation by the private landowner to make them easier on the eye. The Highlands was a special case and frequently received a simplified version, a cylindrical concrete structure that was lighter and quicker to construct through using a tubular mould. These pillars are charmingly called Vanessa Pillars, derived from the company Venesta who manufactured the tubes (and still producing commercial washroom fittings to this day).

In addition to pillars, existing prominent structures served as trig points, for example, there is a brass bolt in the roof of Liverpool Cathedral amongst many other church towers and spires; electricity pylons, lighthouses and water towers also served admirably. Other, much smaller curiosities include Curry Stools (named after the designer), which was a dome for a theodolite, attached to metal rods inserted into ground too soft to support a pillar; and in 1784 the very first triangulation baseline was established on Hampstead Heath by Major General William Roy who used cannon barrels as markers.

The Ordnance Survey no longer maintain the majority of trig points, many not having seen any maintenance since the 1970s, because their purpose has been superseded by GPS technology. As a result, many have been lost, or moved and with increasing urban development some trig pillars have actually ended up in domestic gardens.

Incredibly, the indefatigable hill bagger Rob Woodall has visited all 6,200 surviving trig pillars finishing his fourteen-year project in 2016, from the highest atop Ben Nevis to the lowest at Little Ouse on the Fens at 1 metre below sea level. However, some are still being found so, in addition to his endless exploits, already having climbed all the Munros, Corbetts, Marilyns, Tumps and 1,000ft hills, Rob has to occasionally nip out to bag the latest uncovered trig pillar!

This feature has avoided in depth technical discussion. However, for more information on the fascinating world of trig points and trig baggers, these sites are recommended for further reading. Fill your boots!