Black Combe – Lakeland by the Sea

Black Combe is an outlier, the elephant in the room of the Lake District Wainwrights. It is an isolated sentinel occupying the south west tip of the National Park, yet linked by continuous high ground to the Coniston range, whose mountains jostle for attention amidst the celebrated heights of the national park. Black Combe shrugs off stardom, you take it or leave it, nonetheless, the hill presents a bulky presence that cannot be ignored. And of course, it is hill, not a mountain, standing thirty feet short of the magic two-thousand-foot height distinction. For this reason, it would have given Wainwright a slightly easier conscience when he excluded Black Combe from his list of mountains in the Lake District. Thereby, when choosing a boundary that did not include the considerable dog-leg to Black Combe, Wainwright could conveniently draw a straight line from the outflows of Ennerdale Water and Wast Water to Coniston Water, which looks neat on a map, although produced a topographic anomaly, for there is much hill country outside this delineation. Fortunately, the grand old man of the fells was able to redress the omission with his ‘Outlying Fells of Lakeland’ volume, in which Black Combe provides the loftiest point.

The name Black Combe derives from the dark rocks exposed by a glacial corrie, scooped from the eastern face of the summit ridge, a striking contrast from the otherwise whalebacked stance of the hill. Away from this rugged aspect, the fell is a grassy mound seen in conspicuous solitude from afar. It amused me to read in Wikipedia that Black Combe can be spotted from the tip of the Wirral Peninsula and one wonders how many local residents have been inspired to climb this distant landmark. On the subject of peninsulas, the hill overlooks the most westerly of the Lake District Peninsulas. Many people will be intrigued by the designation of these peninsulas, having been tempted by the promise of interest by the large, brown tourist signs that advertise their existence when approaching from the M6 motorway. Incidentally, I am also amused that one of these signs is incorrectly spelt ‘Peninsular’, as seen when approaching on the M6 southbound carriageway. Whoops!

However, the grand announcement comes to nought as the signs become absent when the peninsulas are actually reached, and you will find little documented tourist information to inform you what and where they are. You’ll need to look at a map.

The map can be zoomed in or out to change the scale

It is a surprisingly long drive to Black Combe when approaching from the east. Much of the rest of Lakeland could be reached in a shorter time, although this remote atmosphere adds to the appeal and is an important factor in my designation of Black Combe as a ‘Worthy’. Naturally, the ascent also needs to be meaningful and, bear with me here as this may not initially make sense, but it is worth climbing Black Combe simply for the descent, which is an absolute delight. To explain this, we will revert to the advice of Wainwright. He describes four routes of ascent and declares the path from Whicham as being the best, which he furthers by ‘walkers who object to treading the same ground twice can combine the route with one of the other three given, but in this case the Whicham path should be reserved for the descent’. I concur without reservation as it is a delight, even though the views that predominate are not of mountains but the coast, nevertheless, this creates another distinction for Black Combe as being a seaside hill, the only one to warrant such a title in the Lake District.

I have been up Black Combe before and the date is in the log that I kept when I was an active climber. It was 21st November 1988. Today, I cannot remember anything about the ascent and my journal provides zero assistance, as I recorded no details of the route taken. Now, thirty-five years later, I was certainly due for a revisit to assess the qualities required for inclusion into the Worthies. The forecast was good, although Britain was experiencing widespread floods from recent storms and I therefore chose the Whicham ascent through being professed as generally dry underfoot. And indeed it was, although Wainwright’s description as “one of Lakeland’s most delectable fell paths… which other can be ascended in carpet slippers?” has altered slightly in the fifty years since he penned it. It remains delightful, although the path has worn to gravel in many places.

Walkers’ reports frequently comment on the steepness of the initial ascent but it isn’t really and the path is good so altitude is gained quickly. Remember, this may not be classified as a ‘mountain’ but we start from almost sea level, so there are more feet of ascent than for many higher tops. It is therefore wise to respect Black Combe as a mountain all the same. Half way up a wider panorama appears as the angle eases, although for me under what was initially a cloudless sky, it had become rather murkier and the summit was now shrouded in mist. I could see clearly to other heights that were devoid of cloud and I am pretty sure I ascended the only hill in northern England that day to have cloud on the summit.

Black Combe is something of a cloud factory, the summit frequently engulfed where other high tops of Lakeland remain clear. One can only assume this is due to the geographical location forcing moist air from the sea skywards to condense into exasperating mist.

The path across the shoulder that curves around the southern top towards the summit is splendid; dry in all weathers, well graded and affording intriguing views of the Cumbrian west coast (albeit including Sellafield, the nuclear waste processing and storage facility that is generally regarded as Europe’s most hazardous nuclear site).

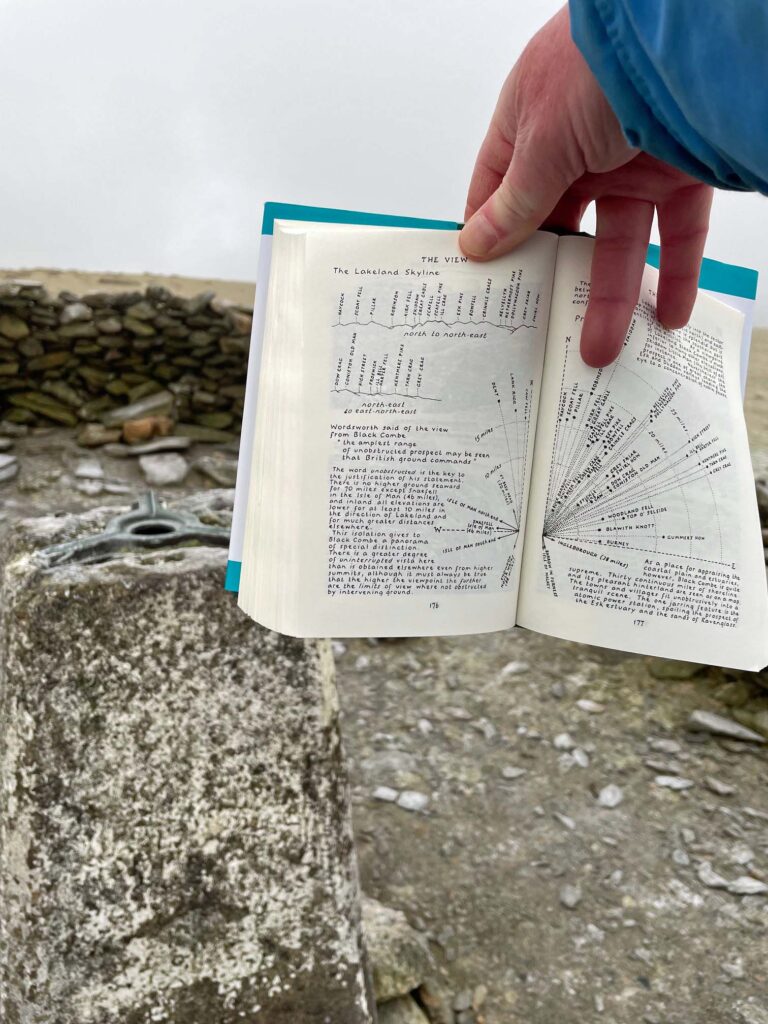

Reaching the summit, the cloud stubbornly remained along with an icy wind that made the sprawling circular shelter a welcome retreat. Bizarrely, in swirling mists, I studied the internet on my phone in order to substitute the mountain views to the north onto my screen. The internet showed them to be excellent, although restricted mostly to the southern heights, which block the fells beyond. Nonetheless, what distinguishes Black Combe is not the mountain panorama but the coastal views, enhanced by those across the sea to the Isle of Man (and doubtless North Wales and Ireland on a clear day).

If you are lucky enough the see the view, look across at White Combe opposite and contemplate the annual fell race that surmounts the hill in March each year. The route is not content with merely employing the Whicham path as, from the top, it launches down into the ravine below and up the other side to White Combe then circuits back around before making the descent back to Whicham. That really is a rather brutal prospect. Another source of amusement are the Organisers’ wry comments for participants at the start of the race “parking is in the start field if dry, but it won’t be dry so you will probably have to park on the main road”.

In William Wordsworth’s time the fell was known as Black Comb and the poet propounded the view to encompass the ‘amplest range of unobstructed prospect that British ground commands’. In truth, the summit trig point is not the best place to take full advantage; the southern top has a large cairn celebrating the coastal vistas at their finest. In this direction, the estuary of the Duddon Sands leads the eye beyond Millom town to the elongated finger of Walney Island and on to the tidal mirage of Piel Island, its distinctive monastic castle like a Cumbrian version of St Michael’s Mount. Many years ago, I delivered wine to the ‘King of Piel’, not for medieval banquets (I’m not that old) but to be dispensed in the Ship Inn, the island’s pub, the landlord of which inherits this honorary title.

Out to sea, in Morecambe Bay, are acres of wind turbines, with more to come as the country strives for sustainable energy and net zero targets. With this aqueous forest of whirring metal poles and the Sellafield nuclear establishment simultaneously in view there is much to ponder, although strangely on the slopes of Black Combe one feels detached; an observer from an ethereal station, not a participant in human dichotomies.

Unless you are making the ascent by an alternative route, stroll beyond the summit to peer down the Blackcombe Screes, the name given to the steep, broken slopes that fall away to the east. As for those other routes, you can find descriptions in the links below. However, the most important thing is to descend by the Whicham path, although not in its entirety… as to best appreciate it views, divert firstly to the south top, then lower down to the prominent nose of Seaness, from where you can continue on a path that rejoins the main route.

For my return drive to the Midlands, I had to divert via Millom as the A595 was closed. This decreed that my total journey to climb Black Combe for this particular outing from home was 360 miles. Naturally, I had other purposes enroute, but this hill had been my primary instigation. Was it worth it? Well, I had not been to the very west of Cumbria for years and the experience was a refreshing change. The ascent (and particularly the descent!) was as good as I had hoped for. It also happened that due to the diversion, when I travelled through Silecroft and had to halt at the railway crossing, I was charmed to see the gates were still manually controlled by a warmly dressed Signalman. This spontaneously transported me back to my youth when, as a train spotter, we used to call the slow west coast line from Barrow-in-Furness to Carlisle the ‘long drag’. It was interminable. However, I was deeply reminded of those unhurried, technology free times. Now to me they seem like halcyon days, although they never felt like that at the time!

Black Combe is rather like that. It’s from an earlier time; ancient, wild and undisturbed – an aloof aerial wilderness and, whilst the modern world forms a part of the view, it’s not on the same page. Black Combe is from millenniums past and we hope, millenniums to come.

For useful route descriptions please visit these pages:

https://www.walkhighlands.co.uk/Forum/viewtopic.php?t=67518

https://happyhiker.co.uk/MyWalks/LakeDistrict/BlackCombe/

http://www.wainwrightroutes.co.uk/blackcombe.htm

Worthy Rating: 71.5

Aesthetic – 22.5

Complexity – 14

Views – 14

Route satisfaction – 14

Special Qualities – 7