Preseli Hills – An enigma of blue stones and golden roads

There is something special in the air amidst the Preseli Hills, a pervading atmosphere of antiquity that captures the imagination, elevating this ridge of gently undulating moorland into a quest for adventure.

Wherever you wander, there is a sense of an ancient past, from the prodigious quantity of prehistoric remains to the powerful links with Stonehenge, Britain’s most-prized megalithic monument, for it was from here that the inner stones of the henge were sourced, either by man… or nature. As you walk the hills your mind will be drawn to examining the hotly debated opposing theories of archaeologists and geomorphologists. More on that shortly, but first let us set the geographical context.

Also termed the Preseli Mountains, this seven-mile chain of grassy tops, peppered by rocky tors, reach no higher than 1760ft (536m), so definitely do not warrant the aggrandised title of mountains, although that is irrelevant to their appeal. I would much prefer to refer to these hills by the Welsh translation, Mynydd Preseli, which is employed on Ordnance Survey maps, yet has never really caught on elsewhere. However, Google would ignore me if I did, so Preseli Hills it is.

The map can be moved or zoomed in and out to change the scale

The hills are encompassed within the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, unusual in that it is the only coastal national park in Britain and that it is divided into four distinct areas. It is the northern part that includes our hills, with the eastern end of the ridge still only ten miles from the sea, and this affinity with the ocean adds an extra dimension to the enjoyment of walking the tops. Even closer to the Irish Sea is a smaller, lower but topographically similar range, capped by Mynydd Carningli, which provides delightful walking on the moorland commons grazed by wild mountain ponies. Do visit these hills while you are there if you can.

As for the main Mynydd Preseli, they form an inviting, well-defined ridge running west to east from Foel Eryr to Foel Drygarn. For their modest altitude, the profile of the hills is a distinctive backdrop throughout much of Pembrokeshire and beyond. It is inconvenient that the B4329 isolates Foel Eryr, as it is integral part of ridge and offers the clearest views of the Pembrokeshire coast. The summit is crowned by an extensive Bronze Age cairn, ten feet high and sixty feet in diameter. However, the high-level car park at Bwlch Gwynt on this road is too tempting to ignore, so most people will park here, meaning you can just nip up and down the hill for completeness.

Ideally, a linear walk is the most satisfying, although requires two cars. There used to be an occasional local bus, although it does not appear to operate now. Having said that, the distances are not great so to turn around at the summit of Foel Drygarn and return is not out of the question, nor are the possibilities of devising circular routes. Foel Drygarn at the eastern end and Foel Eryr at the western extremity are the busiest hills due to their close proximity to a road and both can easily be climbed separately.

As we leave the handy car park at the top of the pass, we are following the course of a very ancient track, known as the Golden Road, reputedly deriving from its use to transport gold mined in Wicklow, Ireland, possibly bound for Wessex, thus providing our initial link with Salisbury Plain. It is also known as Fleming’s Way, which is perhaps an association with the Flemish populations that settled in Pembrokeshire during the Norman occupation. The Golden Road was a Neolithic trade route in use 5,000 years ago and therefore potentially a contender for Britain oldest road, something usually attributed to England’s Ridgeway path, which commences in Avebury. Interestingly, this is arguably where the Golden Road terminated, although the only part of the road ever mentioned is that over the Preseli Hills. Nonetheless, you can begin to see how the archaeologists are drawn to a strong connection with these two areas.

After a very promising start on a solid path, bog takes over for a while. Some of this can be avoided by keeping to the high ground on the right. After a damp hollow and short climb, the Golden Road continues directly on, ignoring any hilltops, as this was not its purpose. Therefore, a diversion is required to attain the first summit, Foel Cwmcerwyn, the highest of the range, with a marvellous prospect of the hills to come. Here you will encounter three Bronze Age barrows. Barrows are grassy mounds that served the same purpose as stone cairns (sometimes the stones overlay a mound), whether for funerary, ceremonial or ritual purposes and they abound on the Preseli Hills. They clearly display that these hills were of much significance to prehistoric people. The barrow on the summit of Foel Cwmcerwyn is crowned by the OS trig pillar atop an oversized concrete plinth.

Leaving Foel Cwmceryn, the path circles round to Foel Feddau, where again the summit is topped by another round barrow, some ninety feet in diameter making it one of the largest on these hills, although being relatively low it’s not that easy to differentiate, especially as the eye is drawn to the walker’s summit cairn. The eye will also take in the extensive views.

Heading due east we encounter the rocky sentinels of Cerrigmarchogion. Welsh folklore will tempt you with the name translating to the ‘Stones of Arthur’s Knights’, these brave warriors having been slain in battle against a giant boar and subsequently petrified in stone. Archaeologists will tempt you with the stones having been a source of (unspotted) dolerite for the inner circle of Stonehenge. The one certainty, however, is that such outcrops will feature frequently on the walk from now on, as a stimulating presence punctuating the barren moorland.

The Bluestone Theories

At Stonehenge, bluestones are the smaller monoliths forming the inner circle within the larger standing sarsen stones. Many of these, composed of dolerite, spotted dolerite and rhyolite have been identified as originating from the Preseli Hills, the link being established in 1921. Bluestone is simply a collective name, not a defining characteristic as many different types of rock was employed, which on the face of it makes any special significance unlikely. Nonetheless, there is a perception that the bluestones were considered magical, despite varying composition and varying sources.

How they were transported is a matter of considerable uncertainty. Quickly skipping over the claims championing giants and wizards, the general assumption by archaeologists and the general public favours the heroic notion of human endeavour, after all construction of Stonehenge was potentially occurring concurrently with the Egyptian pyramids. Whilst our builders didn’t have the mighty River Nile for assistance, passage by river to the sea was a possibility, as rivers were thought to be far larger at that time in history. More recent evidence by the archaeologists as to the precise locations of origin has begun to suggest predominantly overland transport. What further feeds the desire for authenticity of the human transport concept is the undoubted bustle of Neolithic activity in the Preseli Hills.

The alternative theory involves glacial action. This would make the stones glacial erratics, a common sight throughout the country, whereby the bluestones were simply collected by a moving glacier and deposited when the ice began to melt. It is not conclusive that the last ice age actually reached Salisbury Plain but an earlier one might have done. Or at least the stones could have been moved that bit closer.

It is not the purpose of this feature to analyse the theories, merely to ignite a sense of wonder at the past and, whether or not the stones were moved by means of human transportation, there was certainly a lot going on here. It all adds an intriguing dimension to walking amidst these hills.

As the path descends to a shallow col, the spiky tor of Carn Goedog is clearly in view ahead on the left. It is worth a detour for closer inspection in itself, even without the latest claims that this was the precise site from which the spotted dolerite bluestones were sourced. The remote location only helps to build the atmosphere of mystery, although the clear action of winter’s freeze and thaw cycle shattering the rocks is also a bold statement of nature. Incidentally, a few miles to the northwest, at a lower level, is Craig Rhosyfelin, the place where archaeologists now claim the rhyolite bluestones were ‘quarried’.

Gently ascending to the crest of the next hill, we arrive at more rocky outcrops, Carn Sian and Carn Bica, although the prehistory prize hereabouts goes to Bedd Arthur, a stone circle, just beyond. Apart from being the actual grave of King Arthur (fourteen other location claim this distinction), it is an intriguing monument consisting of thirteen stones, each around two feet high and set in a rough oval. The Welsh national monuments database, Coflein, describes it as ‘explicitly ambiguous’, although survey work by Stonehenge experts has optimistically compared the setting to those of the bluestones at Stonehenge, with both aligning to the midsummer sunrise. Unfortunately, the date of the monument has not been established, so the significance of Bedd Arthur is mostly due to gut-feeling, which in these parts is naturally influenced by isolation, Celtic mythology and Neolithic fervour.

The concentration of tors increases, scattered liberally across the moorland landscape, your eyes darting from one to the next, culminating at the largest, Carn Menyn, occupying the summit of the next hill, just a mile or so beyond and only involving a couple of hundred feet of ascent. These hills are rarely tiresome exercise.

Carn Menyn is an impressive formation; a seemingly ideal source of bluestones for Stonehenge, and indeed it was suggested to be the major supplier of spotted dolerite until recent research nominated Carn Goedog as the principal collecting ground. Undaunted, it stands proud amidst an explosion of rocks. Weave your way through this enigmatic boulder field, some of the stone having clearly been worked by the hand of man, whether in prehistoric times or to serve as a farmer’s gatepost. Nevertheless, amongst the debris of this giant’s stone throwing contest lies a genuine Neolithic chambered cairn, a river of stones running from its door. There is an enormous capstone with a collapsed chamber beneath, which was thought to be a communal burial place.

Clamber to the highest point of Carn Menyn to scan the way ahead, the view west dominated by the most distinctive, separate and fascinating of all the Preseli Hills, Foeldrygarn – the three-cairned hill. Foeldrygarn is the final and lowest top on the ridge and requires a detour from the Golden Road to reach it. Ironically, you depart the ‘road’ at what is probably the most manifestly historic part of the path, where an embankment follows the line of the route, although the embankment itself is not prehistoric.

Once you reach the summit, the name of the hill becomes clear, with three vast Bronze Age cairns dominating the scene, built some 4,000 years ago. The isolation of the hill with a 360-degree panorama attracted the establishment of an Iron Age hillfort a millennium later, the builders respectfully leaving the cairns intact. It is believed that up to 270 huts occupied the broad summit, indicating a substantial community.

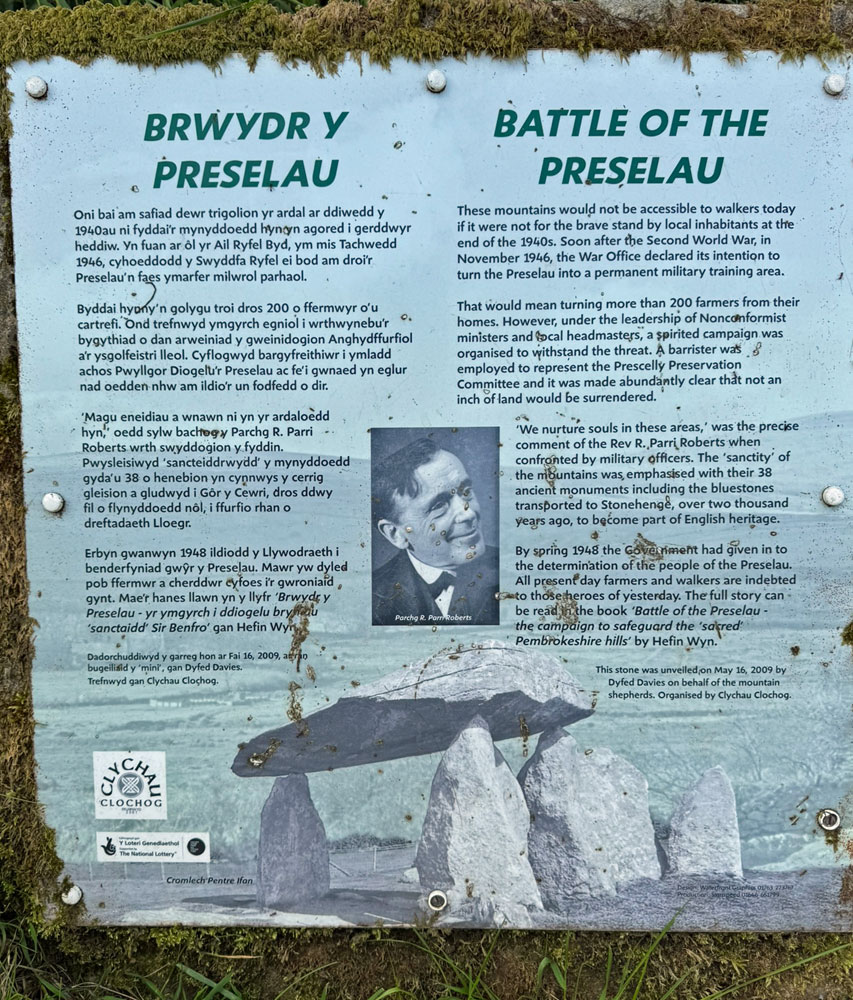

This is an emotive location to conclude the walk along the Preseli ridge, although if the MOD had got their way, public access may have been restricted throughout the whole range. In 1946 plans were afoot to capture this land for military training, but a spirited campaign thwarted the proposal, by emphasising the cultural importance of the district, particularly by citing the prehistoric significance of places such as Foeldrygarn and, of course, those ever-present bluestones. In conclusion, whatever the precise connection between Preseli and Stonehenge, it undoubtedly saved the day for our freedom of these hills.

Worthy Rating: 67

Aesthetic – 21

Complexity – 10

Views – 15

Route Satisfaction – 13

Special Qualities – 8

While you are there…

There are several excellent stretches of coastline within the national park. My particularly favourite section is not all hilly but offers arguably the greatest concentration of inspiring coastal features in Pembrokeshire, if not the whole of Wales.

The entire area around Bosherston and the Stackpole estate is worth visiting, with the western half from St Govan’s Head to the Green Bridge of Wales being especially dramatic. Beyond here is the Castlemartin Firing Range with no public access and even this recommended stretch is usually only open at weekends.

Above left: Huntsman’s Leap, a spectacular inlet (Geo) – Above right: walking above a natural arch

The terrain is remarkably flat; a horizontal shelf suspended around 50m above the sea. To best appreciate the walk, stick as closely as possible to the cliffs, exploring every headland. Occasionally backtracking is required when an unexpected intrusion by the sea is encountered, in the form of geos and blow holes, creating breathtaking landforms.

The rock hereabouts is Carboniferous Limestone, subject to the usual dissolution by water, creating sink holes and caves. Add to this the erosion by waves and the result is a fascinatingly complex coastline.